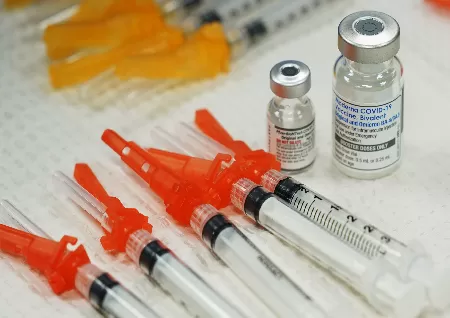

It's not too late to get a COVID booster especially for older adults

Even for older folks, it's not too late to acquire a COVID booster:

When the COVID-19 vaccines were initially made available two years ago and people were rushing to receive their doses, the U.S. had come a long way.

Many people today disregard the requirement to purchase current boosters. Only 15% of those who were eligible for the COVID booster dose that specifically targets the omicron version have received it, a rate that is even lower than the flu vaccination adoption rates, which are infamously low. Vaccine fatigue has reportedly spread to other doses, including those given to prevent measles and polio, according to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey.

As the executive director of the Association of Immunization Managers, Claire Hannan assists immunisation officials from all 50 states in managing vaccine programmes, and she adds, "That is quite alarming."

In order to understand how we should all be thinking about COVID vaccinations right now, NPR spoke to specialists in immunisation, health communication, and public health as the country struggles to finish its third pandemic year.

- Recognize that immunisations remain an effective tool:

We now have answers to many of the questions that were unanswered two years ago regarding the new COVID vaccines. Do we require more shots than two? Yep. Will protection last for a long time? No, antibodies lose strength with time. Is it possible to contract COVID again after receiving a full course of vaccinations? Yes, given that the virus has continued to evolve and produce strains that can partially evade the vaccination, it has grown more plausible than it was when the pandemic first started.

These dismal responses might have decreased interest in the most recent batch of COVID boosters. However, the CDC recommends that adults and the majority of kids get the booster. Additionally, scientists stress that vaccinations continue to be a critical strategy.

to safeguard people over 65 and those with underlying medical issues, who are most at risk of developing a serious COVID infection.

"It's really extremely important that [people] recognise the significance of getting vaccinated and making sure they stay up to date on their boosters," Hannan adds, especially those who are at high risk.

The availability of vaccines, effective therapies, and the high prevalence of infection all contribute to preventing hospitalisation. But COVID still claims the lives of about 2,500 people per week in America.

The CEO of Immunize.org, an organisation that promotes vaccinations and educates the public about them, Dr. Kelly Moore, adds that she personally dislikes needless suffering and death. According to a recent Commonwealth Fund report, the immunisation programme saved more than 18 lives.

to safeguard persons over 65 and those with underlying medical issues, who are most at risk of developing a serious COVID infection.

3 million fatalities and 18 million hospital admissions in the United States were prevented, saving the nation more than $1 trillion.

We still need to use an efficient instrument that can significantly reduce suffering, hospital stays, and fatalities, according to Moore.

2. Distribute vaccines where it matters most:

Focusing efforts on those who are most at risk, particularly seniors, is one way to combat vaccine fatigue. Only 35% of seniors 65 and older have had a current booster. People in this age range make about 75 percent of COVID deaths in the U.S.

According to Hannan of the Association of Immunization Managers, a significant effort was made to visit nursing homes and administer vaccinations to everyone when vaccines first became available. She claims that no longer holds true because everyone has varied schedules for when they need a booster, in addition to low demand and inadequate infrastructure. She explains, "You go there one day and you might immunise a few people."

The strategy for public health is now evolving. For instance, the CDC is undertaking a project to place several single-dose vials in long-term care facilities that have the appropriate storage equipment, according to Hannan. In this approach, even if just one patient of the facility needs a booster shot, nursing home staff might quickly administer the shot by removing a single dose from the pharmacy-grade refrigerator.

Sandra Lindsay advises individuals to consider their grandmother as the winter holidays approach and they congregate with loved ones. As a critical care nurse, Lindsay was the first person in the US to get the COVID-19 vaccine in December 2020. Today, she works at Northwell Health in New York as vice president of public health advocacy.

She asserts that "we all have a responsibility to our loved ones." "Keep to your home if you are ill. Grandma, as a Christmas gift, take her to get immunised."

3. Pay closer attention to worries:

According to Cynthia Baur, director of the Horowitz Center for Health Literacy at the University of Maryland, one of the reasons why people aren't rushing to get immunised now is that they don't believe COVID-19 poses a significant risk any longer.

People must believe they need it and that whatever is going to happen will be terrible enough that they should act, according to her. They don't at this time because restaurants are open, people are gathering and shopping outside, and immunisation is currently available.

In Maryland, Baur has worked with community health workers who are pounding the pavement and chatting with people about vaccinations. According to Baur, "I don't think we or anyone else working on this issue has found any one message, fact, or phrase that is kind of genuinely influencing hearts and minds.

4. Make immunisations less frightening:

There are numerous strategies for overcoming vaccination scepticism, such as concentrating on misinformation, partisanship, or public health confidence. According to Moore of Immunize.org, "I choose to take a slightly different approach, which is to look at ways to improve the immunisation experience."

She notes that about 25 percent of Americans are frightened of needles. "How many of those refusing to get vaccinated are citing reasons like "I don't want it," "I don't have time," or "I don't think it works"? How many of them truly need that as a justification?"

As getting immunised can be particularly stressful and upsetting for those with autism, she claims that the Autism Society for America has been a leader in developing measures to assist families and children with autism. They suggest several easy, affordable solutions, such as using headphones and listening to your favourite music, or employing a little plastic "shot blocker" to lessen the pain of the shot.

When I took my 7-year-old daughter Noa to obtain her bivalent booster, I recently tried a variation of this. (Children are more likely than adults to fear needles—more like 2 in 3) I obtained a back pain relief over-the-counter lidocaine patch from the pharmacy and customised it to fit her bicep. I left it on her upper arm for perhaps thirty minutes.

I then outlined the patch on her skin so the immunizer could administer the shot there. Noa said that the shot didn't hurt and expressed her joy and pride at not crying. She also requested that we use it for each subsequent photo.

She notes that most people do not receive vaccinations through the mass immunisation programme that emerged during the pandemic. If a result, as those systems shut down, it could be time to refocus on healthcare professionals like doctors who can build a rapport with patients and genuinely hear their worries and inquiries.

According to her, the Autism Society for America has been developing innovative methods to support families and children with autisget immunised because it can be particularly traumatic and stressful for those with autism. They suggest several easy, affordable solutions, such as using headphones and listening to your favourite music, or employing a little plastic "shot blocker" to lessen the pain of the shot.

get immunised because it can cause anxiety and distress in autistic persons more than other people. To make the shot pain less, they suggest wearing a little piece of plastic called a "shot blocker," using headphones, or listening to your favourite music.

When I recently took my daughter Noa, 7, to get her bivalent booster, I tried a variation of this. (Children fear needles at a rate closer to 2 in 3 than do adults.) I went to the pharmacy and purchased a back pain relief over-the-counter lidocaine patch, which I then customised to fit her bicep. About thirty minutes before we departed, I slapped it on her upper arm. I then outlined the spot on her skin with a line so the immunisation could be applied.

Give her the finger there. Noa said that the shot didn't hurt and expressed her joy and pride at not crying. She also requested that we use it for each subsequent photo.

Related queries to this article

- COVID booster

- COVID-19

Read more articles and stories on InstaSity Trending Topics.